From the first note of the first frame of The Social Network we are immersed in David Fincher’s senses. The soundtrack roars immediately to life with The White Stripes pulsating guitar riff on “Ball and Biscuit.” We are in a darkened bar. The characters are talking so fast you can barely make out what they’re saying. You might not get what they’re saying but your senses have already come alive — the words match the music, the editing matches the words and good luck figuring out what’s coming next.

But then the rattle of Aaron Sorkin’s dialogue. “Did you know there are more people with genius IQs living in China than there are people of any kind living in the the United States?” “That can’t possibly be true.” The two young stars face-off. One is talking a mile a minute with a mind faster than anything else in the room. But he’s getting it back pretty good from the girl sitting opposite him. And then he drops it, “How do you distinguish yourself from a population who all got 1600 on their SATs?”

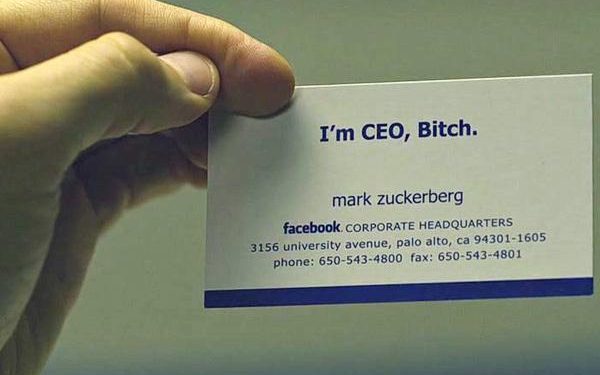

He’s talking about China, he’s talking about Harvard, he’s talking about himself. As Mark Zuckerberg bombs out with his girlfriend what is important about this scene is that he can’t talk to girls. Either his arrogance or his smartness prevent him from doing so. Erica breaking up with him doesn’t necessarily drive him to do what he does in the next hour and a half; it’s his inability to talk to her. This theme repeats, as do many of the film’s themes – Mark wonders about Eduardo’s relationship. Mark wonders about Sean Parker’s relationship with his old girlfriend, with an underage intern. His inability to communicate is both what frustrates him about himself and what drives him to eventually create a communication platform that does the heavy lifting for you.

Three forces pound you at once: Fincher, Sorkin and Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross. The music drives it. No, the editing drives it. No, the directing drives it. No, the script drives it. Welcome to the world of The Social Network.

And yet, as we get ready to close Oscar season, Fincher will be the only director in Oscar history to have won as many critics awards for both Picture and Director without also either winning the DGA and the Oscar, but usually both. It is a dubious achievement but somehow, knowing what I know about Fincher, it’s not going to bother him as much as it bothers us, the people who watch the Oscar race.

It shouldn’t bother us because we’ve all seen the many directors who were never “likable” enough to win Oscars, or never made movies that could appeal that broadly to the voters, Hitchcock, Fellini, Altman, Kubrick, Lynch — the list goes on. Fincher will be in good company when the 6,000 Academy voters put their support behind the much easier to digest and altogether more emotional British film, The King’s Speech — a movie that is so polar opposite the Social Network one can’t help but stare blankly at the irony of it all.

I’d heard Fincher wasn’t a “kisses babies” type. I’d heard he was cold and meticulous in his work, a perfectionist, and not someone who doles out the charm, humility and charisma like, say, Danny Boyle or Kathryn Bigelow or Steven Spielberg or Tom Hanks. Fincher, I was told, is an outsider.

So when I got a chance to interview him a couple of months back I was a tad nervous to meet him. He was flying in and out, filming The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo with Rooney Mara. His offices were quiet, well designed in what looked to be a converted movie theater. High ceilings, minimal art on the walls, much quieter than the busier Hollywood Blvd outside. He was in another interview and my scheduled twenty minutes with him were starting to evaporate. He was supposed to leave by a certain time and I was his last interview.

I’ll keep it really short, I thought to myself. Just a couple of questions about the numerous takes, the editing, the lighting, the cinematography, Trent Reznor. “Okay, you can go in.” I was brought into what appears to be a conference room. A long table with these round glowing orbs hanging from the ceiling. Fincher came in carrying some papers and an ipad.

Far from the persnickety prick I was expecting, he was disarmingly shy, politely shook my hand and sat down. I was worried about the time constraint so I just asked him a few casual questions — which he answered kind of quietly. So where was this famous ego I’d heard about? It wasn’t there. He could have been an English teacher or a waiter.

After about twenty minutes he started to relax a little, finally, and I was able to get him to talk more freely about the film.

“Just kick me if I’m repeating that stuff,” he tells me. One thing you should know about Fincher is that he says Fuck a lot, specifically “fucking.” As in, “but I knew I couldn’t go into Cambridge and shut the fucking place down.”

The Cambridge he’s referring to is, of course, the notoriously private iconic enclave that didn’t want Fincher and his greasy crew anywhere near their ivy walls.

“I wanted to kind of roll with it because they put off all the decisions weeks and weeks and weeks, only to finally say, ‘There’s no interest in having you here at all.’ And then you say, ‘Well, why didn’t you tell us that to begin with?’ They said, ‘Well, we kind of did, but then we told you we would think about it. It was your fault for hoping.'”

A movie about Harvard that isn’t filmed at Harvard. A movie about Facebook that isn’t about Facebook. How do you explain the Social Network to people? It doesn’t fit into any box neatly; it isn’t a formula that sets you up to know a familiar story, to see something you’ve seen a hundred times. People who aren’t moved by films that show anything less than idealized versions of humanity have a hard time with it; they don’t admire the Zuckerberg, the Facebook. And the cruel way Zuckerberg moves his chess pieces in order to get out in front of the Winklevoss twins and any potentially competitive dot com turns people off. But those of us that revel in themes like this and humor so blackened you could almost paint the walls with it find the film endlessly fascinating. It’s really the way it defines the way many of us live and our notions of community now, the irony of the person who invented it, how he invented it and how we now think about “friends.”

But nothing about The Social Network is touchy feely, the least of it its director. While Aaron Sorkin and Jesse Eisenberg have been chatting amiably at parties and to the press, the film’s notoriously media-shy director has been off filming [The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo], seen sitting on his hands writhing in agony at the Golden Globes, just not into the whole “awards thing.” It’s fitting for a director who IS uncomfortable to make films that make us FEEL uncomfortable, something Fincher readily admits he aims to do.

“So, I’ve said this before, but if you were there, if you were just trying to separate people from ten bucks — and that’s what most movies are trying to do; that’s what most movie executives are trying to do. Let’s try to separate you from your ten dollars. Those aren’t the movies that I make. Hopefully. Ideally, I want to separate you from twenty-four dollars. I’d love for you to buy the DVD and watch it thirty times.”

When I tell him I’ve already seen The Social Network at least twenty times (but maybe closer to thirty — something one should never admit out loud) he laughs a little and then looks at me like I’m out of my mind. “I think you need an intervention,” he says. Fincher’s reluctance to describe his own film with the same extravagant praise as many critics have done would at first seem to let some of the air out of the publicity party balloons. Apparently Fincher didn’t get the crash course on how to act self-important.

Fincher speaks bluntly. His sentences, like many of his takes, don’t linger around too long. But that makes his answers seem more clipped than they sound in person. “I like to create a situation where there’s no wrong answers. There’s just the ones we’re going to use and the ones that we aren’t. It doesn’t make any sense to me to bring people in and then treat them like trained cats.”

Fincher takes a lot of grief for his multiple takes of a scene. The old guard of Hollywood has long since been resistant to directors who push the envelope of what the medium is capable of, particularly when it’s being done at a major Hollywood studio. No one right now is aware enough of how unusual this year has been in terms of the directors taking the risks they’ve been taking, their films making money, and all without compromising the richness of the story. Everything in The Social Network is there to service the story, which is partly what makes it such an enjoyable sit on repeat viewings.

He wanted to correct the notion, though, that the opening scene took 90 takes. Technically, it did, but it was split up and there were many different set-ups. He said when you’re shooting in digital it’s a lot like shooting with a digital camera – you take a lot of shots because you know you can throw them away and keep the good ones. In the old days, you’d have to wait for the dailies, look at them much later and then decide what was worth keeping. But with digital you can have the luxury of shooting more stuff and discarding as you go.

“So, the last two or three takes of the fifty-fifty is what you end up using. You throw the other takes away. Then you go forward into the over-the-shoulder and now he’s reversed in that set-up. By the time you get to take seventeen you go, ‘wait a minute, maybe he should try this.’ Now we know this is not going to cut with the master, but if we have her line overlap him on this line then we could, you know, tighten it.”

Fincher and his editors, Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall, edited and culled as as they went along, an easy, ego-less collaboration where Fincher had writer Aaron Sorkin in meetings and on set to help the film, connect all of its tentacles, find cohesion. Fincher’s collaborators – the editors, cinematographer and sound guys, even the costumer, know him pretty well, he says, so that they can eliminate stuff early on they know he isn’t going to want. The editors pared down continually while filming was underway, as uneven scenes were streamlined so the essence was emphasized. These spontaneous course-corrections enabled the actors to find deeper meaning to throw-away lines of dialogue. If you watch The Social Network enough times you will start to hear and see things you couldn’t have gotten the first time through. You almost want to stop the movie and rewind it over a part, “did he really just say that?”

One of the marvels of the film, though, is how Fincher used his most significant collaborators, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. Their music seemed cut to the film, timed perfectly to the dialogue and editing. When I asked Fincher about this he told me that Reznor and Ross sent him the music and they cut the movie to it.

“And then we would start cutting to what Trent had sent to us and invariably it was making everything shorter. It was making it faster, which was a good thing because we had a 162-page script.”

Fincher likes to get a rough cut in the can that’s a lot longer than what the film will eventually be. But The Social Network was a different game entirely, “We went down on Saturday, we’d been cutting for about eight weeks, took 260 hours of material and had down a pass that was an hour and fifty-six minutes. I called the editing room and I said, ‘We’re going to screen this tomorrow right?’ They said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Okay and how long is it?’ They said, ‘It’s two hours and fifty-six minutes.’ I said ‘well, that makes sense. Two hours and fifty six minutes. That’s about right. Yeah. So we might take fifty-six minutes out of it.’

“I hung up the phone and the phone rang about five minutes later and [Angus] said, ‘It is not two hours. It’s an hour and fifty-six minutes.’ I said, “What?’ He said, ‘It’s an hour and fifty-six minutes.’ I said, ‘Check it again.’ He phones me back. He goes, ‘No, it’s an hour and fifty-six minutes.’ And I said, ‘We’ll come in and watch it tomorrow.’

That cut of the film, which probably could have been dumped in theaters and been good enough, was screened and they felt like it was sort of right. But Fincher says the shorter cut and the many different takes and extra footage they had accumulated, allowed them to go back through and comb through the story, to see what needed more background, find what didn’t quite work. “Because originally when we go to Palo Alto, we just started with the guy coming off the roof — aiee! splash! — dropping, instead of the wind up to it. So, there were a lot of little things that we had topped and tailed and it was the first time we’d ever been able to say to Angus and Kirk, ‘Put five minutes back in.’

“So, two days later they had opened stuff up and we looked at it and kind of said, ‘That’s the movie.’ This scene needs to be better and this needs to be more… and this needs to work a little bit harder and we can get rid of the tail of this, but we need to make room for this and we had been planning to do this … And then we saw the movie and kind of said, ‘This works.’ ”

All of their meticulous work, by the way, has paid off. While it might not pay off in terms of Oscars, who cares by this point; great films very rarely, but for every once in a while, win Oscar’s Best Picture.

In the end, though, Fincher more than anyone is aware at how silly the whole thing is, the story of the rise of Mark Zuckerberg. It isn’t a story that is “important” on its own. He feels like Zodiac was the more “serious” story, “Because nobody got shot in the face. Nobody who was there at Ground Zero on Facebook that got shot in the face. And some people in Zodiac got shot in the face.”

The bottom line for him was that “Nobody got hurt.”

The Social Network isn’t a great movie because it tells the story of how Mark Zuckerberg invented Facebook; it is a great story because it beautifully, succinctly and profoundly puts parentheses around human emotion and interaction and an exclamation point after the social networking that is reinterpreting it; to tell the story of how we got where we are — which is a society that is now not five minutes from checking their online communication and finding extreme closeness where there wouldn’t ordinarily be — Sorkin and Fincher had to illustrate it with someone who couldn’t talk to people, not to girls, not to anyone. The only person he could talk to was his “friend” Eduardo.

“You’re best friend is suing you for 600 million dollars.”

“I didn’t know that. Tell me more.”

No one would would ever make the claim that The Social Network was “important.” But its lack of pretention, its acknowledgment of its symbolic representations are more palpable than films that really do claim to be telling things the way they supposedly happened; we can look at ourselves through a magic mirror, or we can look ourselves through one. If given the choice, I will always prefer the latter.

Fincher didn’t believe in making Zuckerberg nicer for the sake of the comfort of the audience, though. One of his best traits as a filmmaker is that he trusts his audience to be smart enough to see what’s underneath, “that people will read into it enough to actually glean what [Mark’s] saying.” They don’t need him to “stop and pet a homeless kitten” to show he’s a good person. The discomfort we feel about him is what Fincher was going for, even though most of the protagonists in his films have been heroic, likable, sympathetic people. The Social Network, though, doesn’t really fit in anywhere in his body of work because it stands apart. Both Fincher and Sorkin came at this in ways they had never come at a film before; it was the genius of Scott Rudin that put them together. A collaboration for the ages.

Before I knew it, fifty minutes had flown by. He’d stayed way too late. I told him that I was amazed at the collaboration on the movie, how everything worked in service of the story — the music, the editing, the sound, the lighting, the cinematography. He looked a little baffled and then said in his plain way of saying things, “Isn’t it supposed to?”

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)