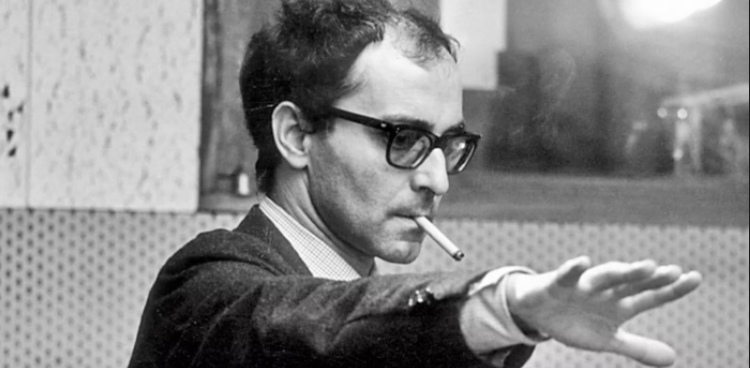

It’s impossible to wrap up the career of Jean-Luc Godard in a single obit/tribute. His life in film is the thing that long form tomes full of deep-dive scrutinization are made of. As a director, Godard has 131 credits and another 98 as a writer. That sort of prolific output is the type that makes your head spin. Above all else, Godard worked.

Perhaps the best place to start is the most obvious: Godard’s breakthrough first full-length feature film Breathless from 1960. Godard, at the forefront of the French New Wave along with Truffaut, Rohmer, Rivette, and Chabrol, entered the arena with a movie that seemed both blasé and effortlessly cool. Breathless made international stars of its leads, Jean-Paul Belmondo and American actress Jean Seberg. To describe Breathless by its plot is an exercise in something well below futility. Sure, on the surface, Breathless is about a small-time thief who becomes a wanted man after killing a police officer, and then ultimately meets a tragic end, but that’s not how it feels when you watch it.

What Godard was doing, along with his fellow New Wavers, was inventing a new film language. One that had no interest in three-act plots or portraying characters in a conventionally emotional fashion. Breathless is aloof, seemingly wayward, and yet, at the same time, completely compelling. For the next decade plus, Godard stayed white hot. Nearly every film he made between Breathless and Tout Va Bien was a cinematic event. Sandwiched between those two films were filmic touchstones like A Woman is a Woman, Vivre Sa Vie, Le Petit Soldad, Ro.Go.Pa.G., Contempt, Band of Outsiders, Une Femme Mariee, Alphavile, Six in Paris, Pierrot le Fou, Masculin Feminin, 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, La Chinoise, Far From Vietnam, Weekend, and The Rolling Stones: Sympathy for the Devil.

Few directors in the history of the medium have accomplished so much in so little time. It’s not just that Godard was a filmmaker who broke the rules, he disregarded their very existence. Take Sympathy for the Devil. On the surface, it might look like a documentary on the making of one of Mick and Keith’s greatest songs — and it is kind of that, but interspersed with the band working the song out in the studio are all sorts of avant-garde touches on the Black Panther movement, Marxism, Mao, Nazis, comic books, and a sizable portion of the film takes place in a pornographic bookstore. I’ve seen Sympathy at least four times, and while I can’t tell you what the fuck Godard was getting at entirely, I still find myself transfixed every time.

And while Sympathy may be a particularly good example of Godard’s boundary defying work, in one way or another, you could say that about every Godard film. You could argue that after Tout Va Bien that,1985’s Hail Mary aside, Godard never really caught fire again. But I also think you could argue that if anyone gave less of a shit how they were perceived than Jean-Luc Godard, you’d need a detective to find them. I won’t go as far as to say that Godard didn’t care at all about the viewer – maybe he did. What I will say is that few filmmakers of his skill level (if any) put the viewer so far into a tertiary concern as Godard did. Godard made films for either himself or simply for the sake of art, first. I’m not sure in which order those two descriptors came, but I feel reasonably certain that it was one or the other. Hell, maybe there’s no difference at all. Because Godard was a very personal form of art taking place in moving pictures. He was a true artiste (yes, with the ‘e’) who cared more for the purity of his vision than what someone might have thought of it once he delivered it to the world. Godard was experimental to the point of being inscrutable at times, and he seemingly didn’t care if you got it or not.

How many filmmakers can you say that about? How many artists in any medium can you say that about?

He wasn’t so much a filmmaker as he was a wavelength. One that at times was impossible to take flight with, and yet notable all the same. Even among his French peers who I named earlier, he was a bande à part. The outsider of all outsiders. While it’s a common and oft-overused phrase to say of a remarkably talented person that “we will never see another like him,” I am quite certain when I say, there was only one Jean-Luc Godard and that there will never be another.

Jean-Luc Godard died on September 13, 2022. He was 91 years old.

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)