Everyone deserves love, and that is the easy lesson that director Maryam Touzani wants to drive home with her beautiful film, The Blue Caftan. It is Morocco’s submission for International Feature Film, and it is more audacious than you might think. The Blue Caftan is a film that first hits your heart, and it could change the lives of many who see it.

(Please note that there are spoilers for the film in this interview. If you prefer to not be spoiled, we invite you to return once you see the film.)

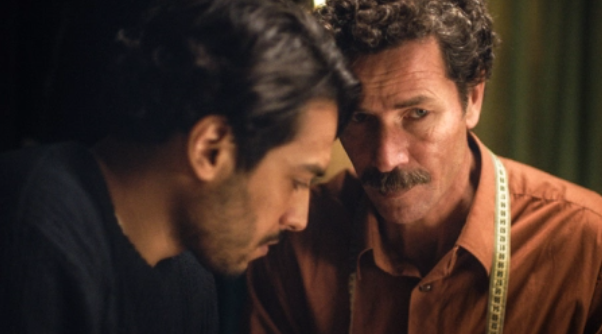

Touzani’s film centers on Halim and Mina, a married couple who own and operate a caftan shop in a medina in Morocco. Some of their potential customers ask them why Halim stitches garments by hand when he can now be helped by a machine, but there is a sense of tradition that Halim is keeping alive by using his hands. They hire an apprentice in Youssef, a quiet, respectful young man who is eager to learn, but it slowly becomes evident that apprentice and teacher have a connection.

It is illegal to be gay in Morocco, and The Blue Caftan being positioned as the country’s Oscar submission is not something Touzani takes lightly. If you are found with someone of the same sex, you can be thrown in jail, and there is currently no protection for gay marriage or even gender identity. Touzani hopes that her film appeals to the humanity we all have inside of us.

“You can be imprisoned for being gay in Morocco. That’s an aberration, and that hurts me deeply,” Touzani said at the beginning of our conversation. “The fact that we are representing the country for the Oscars is symbolically very strong, because it means we can push for change. The laws need to be changed now. This is, above all, a film about love in all its senses, and I wanted to talk about the freedom of love–it doesn’t matter where you are [living] in the world. Representing Morocco is going to make the media in that country talk about this film. Homosexuality is taboo there, and creating a conversation about the mentalities surrounding this is something we are needing to talk about. Cinema can change people’s perception. It is essential for me to talk about this.”

We talked a lot about intimacy. For those of us queer people who have the privilege to live more openly, we can forget how difficult it must be for those who cannot. When Halim is showing Youssef how to stich something or how to lay fabric, their hearts are beating so hard in their chests that we can hear it. This is love found in stolen glances, and there is a sexy moment in the beginning of Caftan where Youssef changes in front of Halim, and he stares at Youssef’s back. Touzani knew that showing this intimacy carefully was essential.

“I wanted to delve into that, and in order to do that, I wanted to be physically close to them while filming,” she reveals. “That is one of the reasons why I wanted to cut off the outside world between their universes. I wanted to be under their skin–or on their skin. When Halim touches Youssef to help him, I wanted you to be affected by that touch. All these supposed insignificant things have true significance for these characters. I wanted to strip myself of any unnecessary things and go into the essential beats of the scene and the dialogue. These gestures and details teach us a lot about what these people are feeling at any given moment, and getting as close as possible was necessary. Intimacy is the key word. I never wanted to be voyeuristic, but I wanted you to be close enough without being too close. Sometimes I wanted to be looking in from the outside, so we could see them evolve.”

After Halim and Nina are informed that there can’t be any other fighting / relationship is reignited / joyous / teasing in bed

While the film is a love story, this is not about Mina being scorned, and Touzani’s film takes a more positive approach when it comes to Mina’s health. At one point, she is told that the doctor cannot do anything else to help with her sickness, and Halim and Mina realize they need to enjoy the time they have left with one another. We never once question whether these two people are madly in love.

“This section we literally stay with them the entire time in the house. I wanted to be that day-to-day with this couple, because we know, eventually, there is going to be a separation. Halim knows his wife is going to die. I wanted it to be about this couple questioning a lot of things, but what stays is their love. That glue holds everything together, and they needed to rediscover that part of their relationship. We need to understand what bonds these people–Halim loves his wife. There is no question about that. That does not keep him from falling in love with another man, and it touches Mina to watch him fall in love again. She has known for twenty-five years that her husband has had other relationships with other men, but it’s only ever been physical. What she sees in his eyes now is totally different than what she has seen before. I wanted us to understand what holds them together. All the little things Halim does for Mina shows what this couple is really made of.

Homosexuality is illegal, but a learning of sexuality that comes from homosexuality is acknowledged. But never love. Love between men is never spoken of–you simply don’t go there. That is something beautiful that needs to be talked about, and that’s why Youssef and Halim actually love one another. There is a physical aspect, but men loving each other is more taboo than the physical act. How can you condemn love?”

Homosexuality is illegal, but a learning of sexuality that comes from homosexuality is acknowledged. But never love. Love between men is never spoken of–you simply don’t go there. That is something beautiful that needs to be talked about, and that’s why Youssef and Halim actually love one another. There is a physical aspect, but men loving each other is more taboo than the physical act. How can you condemn love?”

One of the best moments of the film is when these three dance around the apartment together. It is a seemingly simple few seconds, but the way Mina looks at both her husband and Youssef speaks volumes. It’s pure.

“She looks at her husband and he is smiling and laughing,” she said. “For her, it’s a moment of truth. It’s her blessing, and she wants to give that to him. Mina wants Halim to love himself as she is leaving. What matters, to her, is that he is happy.”

We do not see the finished caftan right away, and its use in the film should be discovered on its own. The color is so seductive but warm, and the gold embroidery shimmers as if it is respecting the person wearing it. Finding the right garment was difficult for Touzani, but she was able to draw on her own life.

“I had written a certain blue, and I could see it in my head,” she said. “I went around for months, and I had hundreds of little pieces of fabric all over my house trying to make sure I could find the right shade. With the caftan, what inspired Halim being a caftan maker is a caftan that I grew up with. It was my mother’s. I didn’t know at the beginning why I made him a caftan maker, but I did afterwards. I grew up remembering my mother wearing a beautiful, black caftan that is identical to the one that is in the film. Every once and a while, she would pull it out, and I was always amazed. I remember thinking that one day, I would be her age and wear something like she did. I waited for the day that I could wear it. That transmission was so beautiful. I thought that I was wearing a souvenir of sorts–something that bonded me closely to her. She always explained how it was made and how long it took. When I started looking for the embroidery for the caftan, I didn’t directly think of my mother’s one, but every time I looked at different caftans, I was getting closer to my mother’s without realizing it. When I pulled out that caftan, I knew that it was the one. I went to the man who made [hers], and we worked on it together. It is over fifty years old. It’s a treasure.”

Since The Blue Caftan is about life-changing, enduring love, I wanted to know where Touzani sees Halim and Youssef goes from here. Her face lit up, and she smiled so brightly that I could almost see her blushing.

“They are going to accompany each other forever–I strongly believe that. They found each other,” she said.

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)