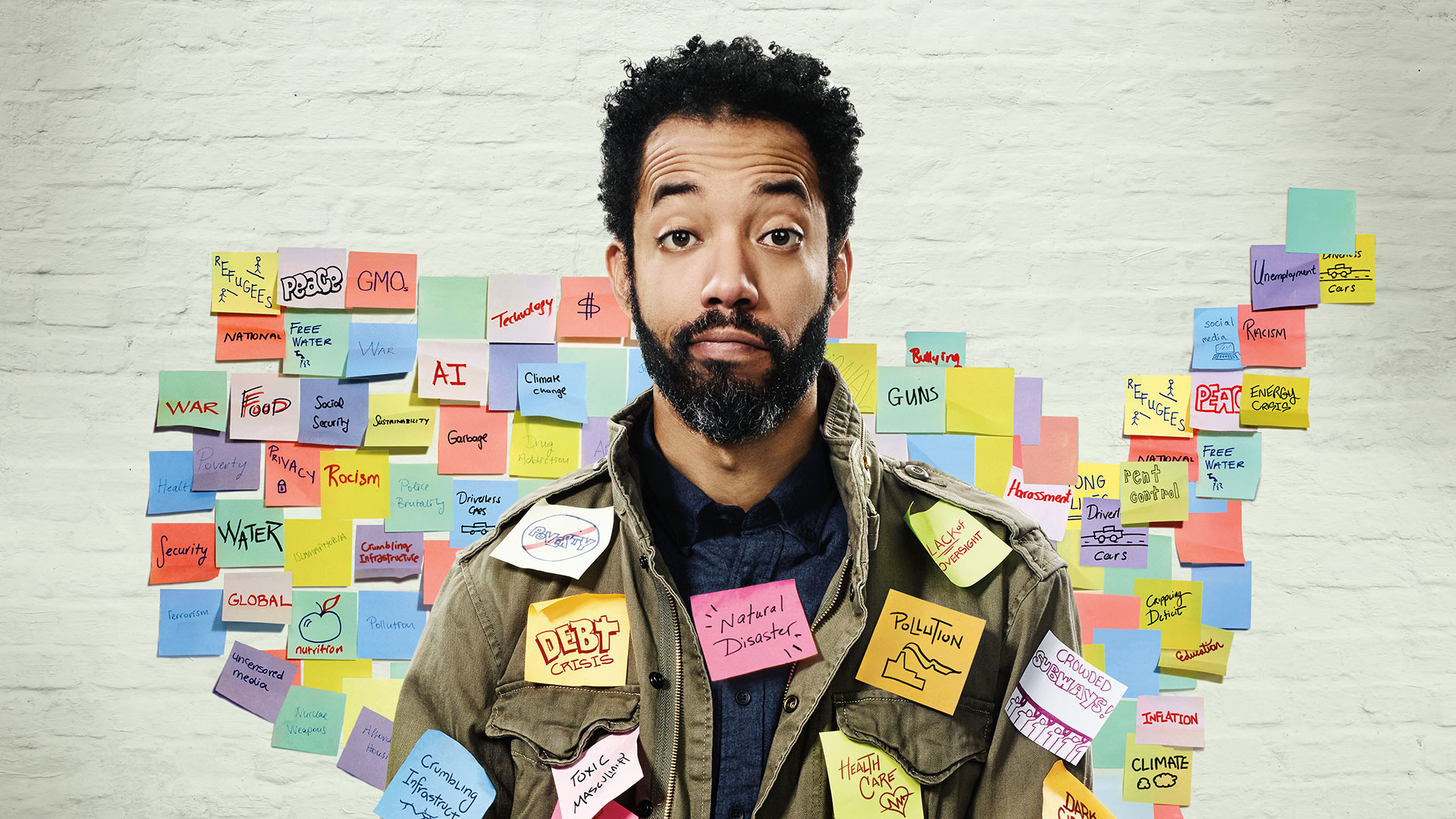

Wyatt Cenac talks about his new show, Problem Areas

Wyatt Cenac’s Problem Areas is a different kind of show. Each 30-minute episode focuses on issues in our country that are particularly challenging, while also returning to a central topic over the entirety of the season. For season one, that topic was law enforcement and policing. The show’s methodical approach sneaks up on you. I found myself unconsciously leaning forward with each episode as it went continually deeper into its subjects.

Mixing in scripted studio pieces, interviews, and man on the street fare, Wyatt Cenac’s problem areas is both entertaining and absurdist, while also being thoughtful and significant. It’s a fascinating mix that I could imagine looking like a less than great bet on paper, but it’s strong sense of humor and tone is a perfect match for the low-key, cerebral humor of its very talented host.

We spoke with Wyatt shortly after the show’s announced renewal about the 10-episode season he just finished, while also looking ahead to season two.

Problem Areas isn’t the typical show you would expect to see on a network like HBO. There’s almost a PBS vibe to it. What inspired you to create this type of show?

The roots of the idea were from the roots of the Daily Show. Covering a fast news cycle. You’d have stories that you’d touch on and then we’d have to move to something else and we’d might revisit it when a similar thing happens. For me, I found myself wondering are their stories that you could live with over a course of a season and talk about it from a bunch of different perspectives and see how things develop or change. I wanted to see if there was a way to bring that type of engagement and entertainment to stories you could stretch out over some weeks.

Was it a difficult show to pitch?

It was definitely challenging because there wasn’t another show to compare it to. We wanted to do a late-night show, but we didn’t want a (live) audience. We wanted to shoot it a certain way and have all these interlocking pieces. A lot of credit goes to HBO for hearing everything and saying, “Oh yeah, we’ll take a chance on that and on you.”

One of the things you did that was unusual, while you cover different topics throughout, the subject of policing is at the heart of every episode. Were you concerned about the ability to sustain that storyline through the whole season?

You always have some concerns going in, but one thing I was looking at as I was approaching it, was the world of podcasts and how serialized podcasts have really grabbed people’s attention. They are not just serialized fictional stories, but also nonfiction. Whether it’s something like S-Town, Serial. or Life and Death of a Mogul. There are all these podcasts that are taking real stories and stretching them out. With that in mind, I saw that and felt like If there’s an audience for that on the world of podcasting perhaps there is an audience that would engage with a serialized, topical show in a late-night format.

John Oliver has a credit as an executive producer on the show. After working together on The Daily Show were you hoping to work together again, or was this serendipitous?

John and I have stayed in touch since we left The Daily Show and we’re friends. We hoped to figure out other stuff we could do together. Working on this show, he’s very busy with Last Week Tonight. They’re in Manhattan and we’re in Brooklyn, so our interaction is not a day to day thing, but it is nice to be part of the same network and working together. Being part of the same team, getting together and chat about our own shows and their creative paths when time permits.

The set is deliberately lo-fi and retro. Even your use of stock footage and animation is very retro to. Which I would think it would make the show harder to pitch. What made you go in such a non-flashy direction?

There are way more challenges in trying to pitch something like this in part because in looking at late night there are so many shows with brighter colors and Lucite desks, and things of that nature. For me, I was trying to figure out something that was perhaps more complimentary to my style. I don’t know if the speed at which I talk and the way that I approach things works with a flashy set and a lot of Lucite furniture. This felt like a comfortable space both for me and perhaps for people to see me and listen to me.

Your sense of humor is a bit more low-key and subtle. Did that make it easier to mix humor in organically while interviewing your subjects about serious matters?

I think there was a desire for a natural rapport. In part because you have people telling their own stories. Whether it’s members of law enforcement, community members, people who’ve been the victim of violence, you really get a great gift when those people are willing to sit down and share their stories. For us, the approach was let’s take in that gift, and with anybody, if you spend enough time with them, there are moments of levity. So, it felt like we could naturally look for those. For me it was both listening and trying to be respectful of the experiences people were sharing, and when the moments present themselves, where it feels like I can add a little bit of levity, I would do that.

Did you feel the stress of trying to make the show conventionally entertaining or were you completely committed to doing the show this way and seeing what happens?

There’s always stress. Especially launching something that was new. So, I felt stress, but I also felt like this was the show that myself and (writer/producer) Hallie Haglund had set out to make. With that in mind if we’re going to make this show and HBO is going to give us the creative license that they did to do this the way we saw fit, I think whatever that pressure is, it turns into let’s put everything we can into making the show as good as possible and as reflective of what our goals are. Because then, win, lose or draw, we at least can walk away saying we made the thing we set out to make.

You mentioned the importance of listening earlier. When you are doing the pieces on set, you are very much on performer mode. However, when you are interviewing your subjects, you seem to truly enjoy taking in their stories. Was switching from being a performer to an interviewer/listener at all challenging, or was that natural for you?

I’m not sure. I feel like that’s a good question for anyone that’s been in a conversation with me. (Laughs). I went into all this with a certain amount of curiosity. I don’t pretend to be an expert on policing, or on any of the things that we were talking about. That’s where curiosity pushed me to want to know more and to want to understand. To understand things, you’ve got to be able to listen.

You really went beneath the surface of policing policies. Things that might look good at a glance, like the community policing program, but when you dig beneath them you find out maybe the program is underfunded, maybe it’s not reaching as far as it should be. When you saw some of the compromises and the fact that some things looked more like PR than a complete effort, were you surprised by what you discovered?

All of it is surprising. Going into any of these situations with people giving you their time, sharing their stories and experiences, I think there’s a part of me that’s going to be surprised by what anyone shares. Ultimately, I try not to get caught up in my own feelings, and I really want to understand, as much as I can, theirs and why certain choices are made, and why certain things are done.

One of the major themes that went through the policing sequences was the need for community involvement in reform. Did you find the level of sincerity coming from the police to be the biggest factor in the success, or lack thereof, of the programs?

For us, making this, the cities that had the most actual, balanced engagement between law enforcement and community, those seemed to be the cities that had the best community-police relationships and were the places that didn’t have as many instances of misconduct or brutality, or just mistrust that you tend to see in the national conversation that happens around policing.

I was impressed by the amount of access you got to the police force.

Me too! (Laughs).

How did you go about reaching out and getting them on camera?

A lot of credit has to go to the field producers. They did a great job of working with our researchers. Those two departments together working together to track down potential subjects and to let them know what the show is and what we were trying to do. There’s a definite skittishness that exists. Especially among law enforcement when camera crews come around. That’s unfortunate, and perhaps says something about an institution that is talking about transparency and accountability, but then not wanting to fully engage with it themselves. Whether it’s an HBO television series or someone with a cell phone.

Considering how much access you got and now that the show is out there, have you received any feedback from the officers and other law enforcement officials you spoke to?

A lot of the producers and researchers have followed up with the subjects and it seems like many have been positive about the experience. I think ultimately the show is focusing on people and institutions trying to change things to help close the divide that exists between law enforcement and communities. I think anybody who’s got a program that they feel really strongly about, they’re going to want to advocate for it. To our benefit, we had people who felt their program, whether it was a restorative justice program, like we saw when we went to Oakland, or a SMART program that pairs up officers with clinicians and social workers, those were programs the people involved with felt a real sense of pride about. I think they want to see those programs spread and see what policing and the criminal justice system can look like.

Of all the programs you covered in the season I thought the restorative justice was the most radical, and probably the hardest to sell. It reminded me of the truth and reconciliation efforts that stemmed from places like South Africa after Apartheid. I had not heard of anything like this in America. Were you surprised to learn about it?

I was. It would be more encouraging if people were more aware of it. I do think when we talk about the criminal justice system and policing in this country, it just feels like this is the system we’ve got, and this is what we do. There are programs like this that have existed outside the US that have been very successful. It’s encouraging to see people doing that work and trying to bring something like that here. While on the one hand it seems very radical, it also seems incredibly compassionate. Especially in a nation that oftentimes tries to wrap itself in the compassion of a Christian nation. There seems to be nothing that is more compassionate than something like restorative justice, and the idea of rehabilitation. So, maybe it’s radical, but it seems more true to the presentation of the society we try to wrap ourselves in.

The restorative justice segment led to what I thought was the most personal aspect of the show for you, and that was talking about the murder of your own father when you were six. You mentioned in that episode you would be open to meeting with the person that was found guilty of the crime. Is that something you would hope to do at some point?

I don’t know if it’s anything I would hope to do. If the opportunity presented itself, it’s nothing I would walk away from. I feel like it’s an interesting conversation to have. I don’t think there’s anything that would come out of it as far as some great moment or answers. For me, it’s not as if I’m looking for some kind of peace. In terms of “I can finally let this rest now.” My interest in it, if I were to chat with the man, I’d be curious to hear his story. I don’t think there’s anything more than that. I wouldn’t necessarily be looking for an apology or even an explanation. To me, so much time has passed, and so much has happened since that moment. Even in trying to understand the idea of restorative justice, part of it was trying to think about what is it like for a person who does something terrible and how do they move forward? Moving forward with so many obstacles before them, does it make them introspective or resentful for being penalized for what they did. Do they see themselves as victims because of the way the criminal justice system is set up? Do they find themselves feeling like a victim even though they victimized someone else?

I thought it was interesting that even without speaking to the man, what you discovered about him through public records, as you talk about on the show, was illuminating in regards to what may have led him to do something that affected your own life so much.

Seeing someone’s life laid out in a rap sheet. It paints a picture. When you look at all the things they’ve done, and you see how they’ve aged over the years, it humanizes a person who prior to that I had not thought about in that way. It’s a strange thing. It’s not about fixing anything, there’s some level of understanding. I feel like I don’t have the proper words for it.

Maybe it just contextualizes it?

Yeah, I think. Yeah, I’ll give it to you. (Laughs). We create monsters when we don’t understand people. And we don’t understand motives. It much easier to say that person’s a monster. You feel like you’ve been hurt at the hands of a monster. The reality is these are people. There’s no justification for why they do the things they do. But in understanding a little more, maybe there are systems that can be created to help prevent those types of things from happening to other people. And perhaps in understanding it can help the individual who was hurt not feel quite so affected or at the mercy of the monster.

Talking about decisions that people make. If we take it to the other side, and look at the police, and think about the blue wall of silence, did you get the sense that they understand when they protect someone on the force who has done something terrible that it hurts their ability to do their job effectively?

I do think the officers I talked to understand it. The challenge is both in understanding it and then have the willingness to speak up. There are things within the job that help to silence officers from speaking up more. When you pull them to the side and have a conversation they will say certain things about “Oh, that was bad”. So, it’s very frustrating that they have the ability to say things off the record, but not on. It seems like whatever that blue wall is the repercussions of going against it have become more terrifying and problematic for officers than whatever frustration or ire they receive from the public they serve.

For the next season, do you want to keep a similar format where you have multiple topics per episode, but there is one overriding subject throughout?

Yeah, we’ll still have one season long topic in season two.

Do you want to tell me what it is or no?

(Laughs) We’re still thinking about it. At this point we are catching our breath after finishing season one. We’re all going to take a little time this summer, relax a little bit and get back into it later in the fall.

The last episode touches on education, which seems like fertile ground.

There’s definitely a lot in the world of education worth looking into. I know once we start digging into it, I know there will be a lot of healthy debates about what we could do for season 2. It’s really been a great opportunity to make the show and I’m excited that we get to keep making more.

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)