When Spike Lee first started making movies in the mid-80s, he was a one-man revolution. His powerful sense of style mixed with his fearless attention to hot button issues announced a major new presence in cinema. And of course, he is black. Unapologetically so.

He was telling stories filmgoers had never seen before in ways that were unrecognizable. His very particular sense of humor, near constant saturation of music, camera work that broke convention, fearless exploration of race in society, and unusual tonal shifts changed the language of cinema.

Sometimes his brash nature overwhelmed the media coverage of his films. Of his era the only major director I can think of who was nearly as polarizing is Oliver Stone. Coincidentally, Spike’s breakthrough with She’s Gotta Have It came in the same year as Oliver’s with Platoon in 1986.

The thing I loved about both was the fact that their films had fingerprints all over them. Their fingerprints and no one else’s. In 18 years, Lee made 17 films. While the quality varied, every single picture was unmistakably Spike. Even adaptations like Clockers and The 25th Hour, as well as his version of a serial killer movie, The Summer of Sam, felt like movies that could have only come from one source.

The breadth of the pictures he created over that stretch is astonishing. Crooklyn was small and intimate. Malcolm X was epic and sumptuous. School Daze was practically a musical. As was Mo’ Better Blues. He made a sports film (He Got Game), a concert film (The Original Kings of Comedy), a remarkable documentary (4 Little Girls), a relationship drama (Jungle Fever), an insane film (Bamboozled), and the genre defying Do The Right Thing.

Even the two lonely misfires of this era, Girl 6 and She Hate Me, were more interesting than most filmmakers’ successes. The failure of the latter did lead to a less certain period of film-making.

Spike followed that commercial and critical bust with his most straightforward commercial film. The terrific heist thriller Inside Man. While the Denzel starrer had plenty of Spike’s stylistic flourishes, it was a film that didn’t exactly feel like it came from the gut. Sure, he Spikeified the film with his unmistakable style, but it felt a bit like a movie that a great director makes to keep the tools sharp while he figures out what he really wants to do.

Coming off the largest commercial success of his career, and the majestic Hurricane Katrina documentary When The Levees Broke, Spike followed up with the ambitious World War II epic Miracle at St. Anna. A complete wash out at the box office and with critics.

While I wouldn’t describe the next few years of his career as “Spike in the wilderness,” let’s just say he was in the meadows for a bit. Oh, he kept working. One thing about Spike Lee is he is always working. Whether its music videos, commercials, television, or on theaters, he let no moss grow underfoot.

On film though, his output became less certain. From 2009 to 2014, he made four films that were released in theaters. The concert film Passing Strange, two micro-budgeted indies (Da Sweet Blood of Jesus and Redhook Summer), and a failed remake of Chan wook-Park’s South Korean classic Old Boy. All of them barely seen and with the exception of Passing Strange, not well considered.

It might be a stretch to say Lee had lost his way, but he had seemingly lost his relevance. It’s not that any of these movies were terrible, or that his skill level had diminished. It’s more that they were wayward. Uncertain.

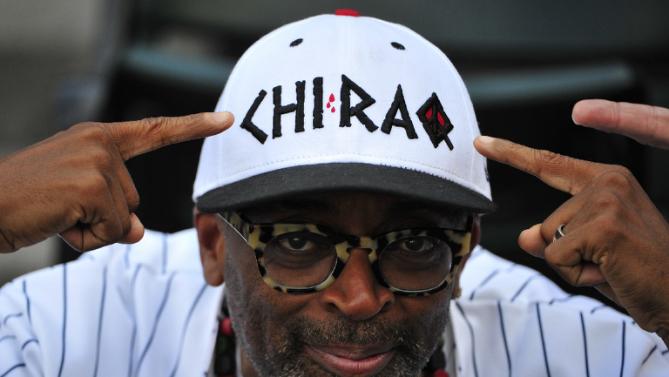

Then in 2015 he made the Spikeiest Spike Lee film in ages. The musical drama Chi-Raq. A film about the gang violence in Chicago melded with the Greek play by Aristophanes, Lysistrata (where the women withhold their charms until the men lay down their weapons of war), and spoken almost entirely in iambic pentameter. Yes, you read all those words correctly. While not a perfect film — it suffered from what I’ve always believed has been Spike’s greatest strength and weakness, too many ideas — it was bold, electric, and often thrilling. There was simply nothing else like it anywhere.

It was unmistakably Spike.

While Chi-Raq received only a limited release before moving over to Amazon’s streaming platform (it was that studio’s first theatrical release), it laid down a marker. Spike Lee was back to doing it his way. Damn the torpedoes and the repercussions.

The reviews for the film were, like the movie itself, all over the map – if generally positive. The box office was non-existent. I imagine more than a few of those who did see it were left scratching their heads. Chi-Raq was no easy meal. It was however, a feast.

Chi-Raq is singular, propulsive, uncompromising. Everything we had come to expect from Lee. Except that it had been so long since he’d given it to us we no longer knew if we’d ever see it again. It would have been a major artistic statement coming from any filmmaker. Who in the world would set comedy, tragedy and modern day societal ills to song while viewing the story through the lens of a play first performed in 411 BC? The truth is, it could have only come from one.

Fingerprints. Once again.

Having seen BLACKkKLANSMAN twice in the last three days, I am more than certain that it belongs on his Rushmore. Next to Mookie, Malcolm, and those 4 Little Girls. KLANSMAN is Spike in full flight. Swimming in all of his Spikeisms. The lush score of Terrence Blanchard. The specific wit of its director. And the lit from within burn of the iconoclastic visionary who we might have forgotten about for a time.

Until he made us remember.

BLACKkKLANSMAN is one of the best films of the year – you can read Jazz’s full review here. It is close to perfect. While its tale is steeped in the past, the echoes of its telling of the true story of the first black detective on the Colorado Springs police department who infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan are sadly and profoundly relevant to the times we live in.

The film masterfully works in DW Griffith’s racist landmark Birth of a Nation and the white power march from last year in Charlottesville — complete with a clip of Trump’s “Good people on both sides” speech. The point the film makes is clear. Things have not changed nearly as much as we’d like to believe.

In some ways that’s the point Spike Lee has been making for his entire career. If you don’t know your past, you don’t know your future. It can happen again. It can happen here. Maybe it never even stopped. It just went underground, this pestilence of racial hatred. It was spoken of in whispers between like minds, greeted with secret handshakes and communicated in knowing glances. That which was hidden is now in the light though. Those that would like to eradicate all they fear. All that does not look like them. They have their champion, and he has emboldened them. They now march through the thoroughfare, chanting and carrying torches.

The good news is there is more of us than there is of them. We just have to show up. BLACKkKLANSMAN is all about showing up, and when you arrive, doing the right thing. Spike Lee has been telling us this story his whole creative life. Do not learn to live with what you cannot rise above, go under, or around. The only way out is through.

It is one of Spike’s greatest films. I don’t know if he would have gotten here without Chi-Raq though. There are moments in a creative career when you can feel an artist making a turn. Or perhaps, in this case, it was a return. This fuck-it-all, I’m throwing it all at the wall crazy quilt of a motion picture that felt like a manifesto as much as it did a movie.

And here is what it had to say.

Spike Lee is making Spike Lee joints again.

Get ready.

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)