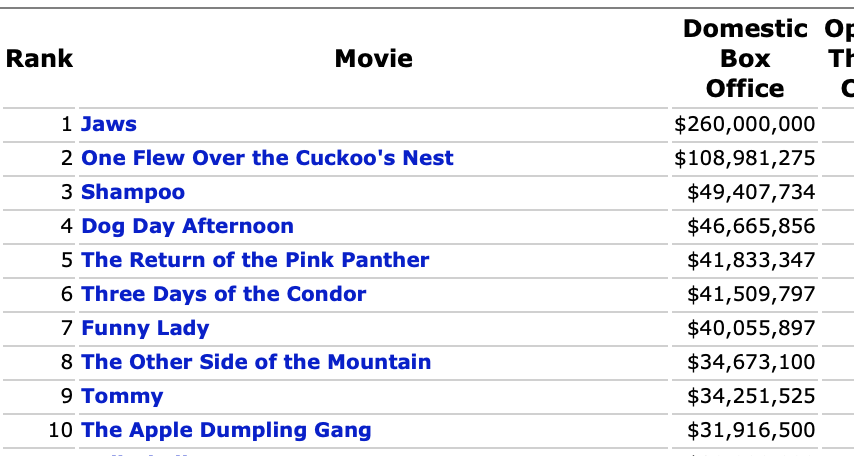

In 1975 Jaws was the number one film at the box office. But after Jaws, the film that sold the most ticketss that year was the eventual Best Picture winner, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Can you imagine that? A movie that popular with audiences and Academy members alike? Here are the top ten films of ’75, from The Numbers:

Dog Day Afternoon brought in $46 million — at a time when movies cost two dollars to see. And look at that, Tommy at number 9. The only trace of a sequel was The Return of the Pink Panther. Hollywood had a problem; studios liked the idea of sequels but back then most moviegoers didn’t respond to sequels. Universal would have loved nothing better than to make Jaws take another chomp out of the box-office, and they tried 3 times, but good luck making that magic happen without Spielberg and the alchemy churned up by the original cast. All the Jaws sequels were dead in the water. In October 1975, Spielberg famously said that “making a sequel to anything is just a cheap carny trick.” As we know, he would change his opinion about that after he joined forces with George Lucus, who proved how to do it right with his followups to Stars Wars, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi.

Making money has always been part of the Hollywood dream machine because of course it has. But it wasn’t always the only dream they chased. So when did things really start to change? Part of the reason was the way the big five studios got quietly absorbed into multi-national corporations beginning at the end of the 1960s. At first nobody in the audience noticed much difference, aside from the fine print in the logos. (Paramount, A Gulf-Western Company. Shrug. MCA Universal? Whatever.) By the time MGM made Network in 1976, only insider observers like Chayefsky cared that the lion of Hollywood had to merge with United Artists to stay in the game.

So when did profit margins become such an overriding goal that Hollywood forever changed to make those margins more reliable? When did studios start to worry more about satisfying shareholders than they did about critics? It happened as soon as those shareholders became impatient with making millions and got their first taste of billions. Check the charts to find that tipping point.

1977. Cue the Star Wars theme:

Even then, things didn’t change immediately — although how voluptuous that first cushy billion must have felt. Blockbusters had been around for a decade or so but anything approaching 10 figures was rightly regarded as an anomaly. Mega-hits on that scale were still outliers, because the formula hadn’t yet been perfected. The landscape would remain unchanged for a few more years.

This is how peaceful things looked in 1979:

So how about 1980? Well, we’re getting there. Another trip to a galaxy far far away gave us a taste of the future:

At that point, nobody but George Lucas and Steven Spielberg seemed to know the secret of making blockbuster lightning strike repeatedly. But let’s give a little credit to audiences too, who were learning how adapt to must-see movie events. Airplane!, Mad Max, fuck, even Nine to Five at number 2. These were movies everyone wanted to see because nobody wanted to be left out of the cultural conversation. Word of mouth had always been the kind of advertising that money couldn’t buy, and especially so when combined with be there or be square.

Hollywood still knew the value of original stories — but those stories require a leap of faith to lure ticket-buyers because good reviews and word of mouth are beyond the studios control. Building a film around a great screenplay and star-power luster is a great way to make great movies but it isn’t a great way to guarantee profit. No, to get those big profits you have to look at a different kind of model — not the old-school Hollywood model of creating and producing art but rather, the corporate model of calculated branding. How do you build brands that customers trust? Well, you have to follow one basic principle: fewer choices, expectations met. Or as Harvard Business Review puts it, if you want to keep your customers, keep it simple.

And simple is what it soon became. Were we there in 1985? Not quite. But we’re starting to see it. Sequels were no longer just cash-grab knockoffs; they were turning into definable formulas. In the old days they would simply put a number next to the title. The fact that such an obvious marketing ploy would be mocked today is a tribute to how fast a sophisticated consumer caught onto it. But back then it still worked, because the whole idea was to sell them what they had before, because if they liked it once they’ll like it again.

From Boxofficemojo:

It wasn’t just movies. The reason we have fewer mom and pop stores, and family-run burger joints across America, the reason you can find the same stores in any town you visit from Portland, Oregon to Portland, Maine is the same principle of fewer choices, more familiarity. Why are we like this? Why do we fall for it? Because it works. I recently visited Portland — incidentally, a place where there are still hundreds of mom and pop coffee shops — and arguably the best coffee in the world. But what cafe was the most crowded? Starbucks. Why? Because consumers have become accustomed to trusting the brand that delivers and have become less willing to take a chance on a unknown quantity. Sad to say, you can’t train a puppy to obey without offering reliable rewards.

When I embarked on navigating motherhood with my daughter 20 years ago, I began to notice how all of her toys had to be brands. My Little Pony or Teletubbies. There were a handful of shows that all of the kids watched, like Sponge Bob. And so the toys and the birthdays and the Halloween costumes were also Sponge Bob. This is our tribe, they said, climb aboard or else miss the boat. Most of those kids have grown up surrounded by ads and signs and cues that make it easy to respond likewise to films that are trusted franchises brands. Big brands. Brands so big that they can block the view of anything unique and small.

So had this shift taken over at the multiplex in 1995? Look carefully and you’ll see sprouts but tentacles have yet to spread.

Was 2000 the point of no return? Not yet, but brace yourself.

The following year, yes, welcome to new reality. We now see what box office would come to be. 8 of the top 10 movies are either sequels or movies that would spawn sequels. Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings were both original stories made from original books. And it might have have ended at that. if neither had made much money. Hahaha, as if. They made a lot of money. A LOT, A LOT, A LOT of money.

Something really dramatic happened between 2000 and 2001 to shift the top box office earners away from adult fare to 100% kid and teenage fare. Just look at the profits. Because you can be sure that’s what the shareholders and studio execs were looking at. When it’s crystal clear that so much money can be made with sequels and franchises and brands, the easiest decision in every corner office is to greenlight more of the same. And what better way to spin off variations on a theme than to latch onto proven treasure troves. Marvel and Star Wars have all but owned the franchise market and they’re now owned by the same company. Disney. Disney cracked the code. Finally — full saturation deep into the brilliant and guaranteed consumer model of fewer choices, expectations met:

Of course, the studios still need to keep a close eye on shifts in audience taste, especially in the era of social media taste-makers. So they carefully beta-test new flavors, to see what works. One thing we know about kids and grownups who think like kids: rub them wrong and they can be fickle as fuck. So they wisely stroke millennials by embedding acceptable messaging, and they smartly tap into the previously neglected half the population by giving women leading roles for better representation. Doesn’t matter than not many actresses have been given the chance to build a star-power brand in their careers. In fact, it only serves to prove that stars don’t even matter any more. One of the lessons of old-school Hollywood has always been this: if they need a star, they can create one. What matters more than any of that is how it’s wrapped, the complete package, the fan experience.

Let’s not overlook the way that history has always shaped America’s hopes and fears, our dreams and nightmares, and the fascinating way that movie screens are a both window and a mirror of the country’s psyche. As much as the movies of the 1970s rose to the top of box-office by tapping into America’s growing sense of uncertainty and paranoia, at least families of that era weren’t faced with mankind’s annihilation. It’s maybe no coincidence that the first year we started taking our kids en masse to see movies where superheroes could always save the day was the same year the twin towers of the country’s invincibility were destroyed. There once was a time when you could make a lot of money by making people afraid to go in the water. These days you can make even more money by helping people escape that fear and dread for two hours,

300 million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars. You can’t make that kind of coin anymore with movies like The Godfather or Apocalypse Now. You sure can’t do it with Taxi Driver or Raging Bull. To get there you have to be fast food, the universal comfort food. You have to be the same five fast food joints that you find at any truck stop off any interstate in America. Fewer choices, expectations met. Instead of exploring something unknown, we want to park someplace that looks like home base.

So don’t be down on Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese who remember what it was like when maverick filmmakers had a great original idea and do things nobody had ever seen before. They were part of a generation that went to the movies for the experience of blowing the minds of those who were unafraid see something that might kick their asses — not to be coddled by the fan experience that they felt they were owed.

I’ve heard complaints that this falls into the “old men yelling at clouds” thing — but to my mind it doesn’t. It might if the cloudscape wasn’t so artificially manufactured, so calculated, so reliable, so automated.

Blockbuster Hollywood can’t turn back now, because look at the profits. They couldn’t even if they wanted to because it’s want the fans want, it’s what the shareholders demand. People want to see these movies and enjoy the quickly digestible comfort of these movies, just as they enjoy their Big Macs. And In n’ Out and all of the branded candy and costumes at Halloween. This is the American religion: brand tribalism.

What the superhero movies sell at the end of the day isn’t new. To give a few humans a superpower boost, tantamount to gods, to defeat evil and triumph, live forever with super strength and wit? These updated and upgraded gods are the only heroes we can trust. Stories like this have been immensely popular since the days of Ancient Greece. At a time when most of us feel helpless to stop the train wreck that is human existence, what better way to escape that than to go back to the Dolby Churches, and the Cathedrals of IMAX every Friday night to worship at the alter of familiar, all-powerful gods?

I don’t blame fans for loving superhero movies. But no one should criticize Martin Scorsese for saying Marvel movies aren’t “cinema” if he’s one of the geniuses who helped America graduate from Herbie the Love Bug to Taxi Driver. If he didn’t have a higher bar for cinematic achievement he would never have endeavored to make Raging Bull, Goodfellas, The Departed, Kundun… and the world be less than it is. As for Coppola, here’s what he said:

“When Martin Scorsese says that the Marvel pictures are not cinema, he’s right because we expect to learn something from cinema, we expect to gain something, some enlightenment, some knowledge, some inspiration. I don’t know that anyone gets anything out of seeing the same movie over and over again. Martin was kind when he said it’s not cinema. He didn’t say it’s despicable, which I just say it is.”

I would not go so far as to say it’s despicable. I do find the corporate branding to be cynical and depressing. And to be confronted yet again with the ultimate truth that human desire is this easy to figure out and pander to — that certainly scares me. The limited choices we now have in our world, how wealth is concentrated into fewer and fewer hands scares me. I don’t blame people for opting out of this world and into one they better accept. I would just say this: enjoy yourself any way you want, but set aside time to think critically. Don’t be such an easy mark. In a capitalist system the consumer has the power. The second that people stop going to see these movies Hollywood will stop making them and start giving us new and hopefully more fulfilling.

Some of us are lucky enough to remember the bliss of what it was like to go to the movies when movies were cinema. Don’t be mad when we wish everyone could experience the same sensation. Viva Scorsese. Viva Coppola. If the current studio system has betrayed us, at least we have Netflix.

![2025 Oscars: Can a Late-Breaker Still Win Best Picture? [POLL]](https://www.awardsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/gladiator-350x250.jpg)